The Deprivation of citizenship under section 40 of the British Nationality Act 1981 is usually on grounds of fraud, false representation or concealment of material fact or on grounds of conduciveness to the public good.

Deprivation of British citizenship results in simultaneous loss of the right of abode in the United Kingdom and so paves the way, for possible immigration detention, deportation or exclusion from the UK.

Section 40 of the British Nationality Act 1981 (as amended) provides a power to deprive a person of his or her British citizenship status.

British nationality law provides for six different types of British nationality status:

- British citizenship

- British overseas territories citizen

- British overseas citizen

- British subject

- British national (overseas)

- British protected person

The deprivation of citizenship powers apply to all six of these categories.

- The Home Secretary may make an order to deprive a person of British citizenship status in any of the following circumstances:

- The Home Secretary considers that deprivation “is conducive to the public good”, and would not make the person stateless (s40 (2); s40 (4));

- The person obtained his citizenship status through registration or naturalisation, and the Home Secretary is satisfied that this was obtained by fraud, false representation or the concealment of any material fact (s40 (3));

- The person obtained his citizenship status through naturalisation, and the Home Secretary considers that deprivation is conducive to the public good because the person has conducted themselves “in a manner which is seriously prejudicial to the vital interests of the United Kingdom, any of the Islands, or any British overseas territory”, and the Home Secretary has reasonable grounds to believe that the person is able to become a national of another country or territory under its laws (s40 (4A)).

- In the second and third scenarios, deprivation of citizenship is permissible even if the person would be left stateless.

- ‘False representation’ means a representation which was dishonestly made on the applicant’s part. ‘Conducive to the public good’ means depriving in the public interest on the grounds of involvement in terrorism, espionage, serious organised crime, war crimes or unacceptable behaviours

The Home Secretary has power to deprive a person of British citizenship in any of the following scenarios:

- She considers that deprivation of citizenship is ‘conducive to the public good’, and would not make the person stateless;

- The person obtained his citizenship through registration or naturalisation, and the Home Secretary is satisfied that this was obtained by fraud, false representation or the concealment of a material fact;

- The person obtained his citizenship through naturalisation, and the Home Secretary

─ considers that deprivation is conducive to the public good because the person has conducted themselves ‘in a manner which is seriously prejudicial to the vital interests of the United Kingdom, any of the Islands, or any British overseas territory’; and

─ has reasonable grounds to believe that the person is able to become a national of another country or territory under its laws.

In June 2016 the Home Office responded to a Freedom of Information request that sought the number of deprivation decisions made each year since 2006.11 The Home Office revealed there had been 81 such decisions and provided the following break-down by year:

|

Year Number of |

Deprivation Orders Made |

|

2006 |

Less than 5 |

|

2009 |

Less than 5 |

|

2010 |

Less than 5 |

|

2011 |

6 |

|

2012 |

6 |

|

2013 |

18 |

|

2014 |

23 |

|

2015 |

19 |

The Home Office response also provided information as to the reasons for the deprivation decisions:

- 36 decisions were taken on the grounds that the Secretary of State was satisfied that deprivation was conducive to the public good (section 40 (2));

- 45 decisions were taken on the grounds that the Secretary of State was satisfied that the person’s registration or naturalisation as a British citizen was obtained by means of fraud, false representation or concealment of a material fact (section 40 (3)).

British passport

British citizens are not entitled to a British passport. The passport does not confer citizenship; it is merely evidence of it. Passports are issued at the discretion of the Home Secretary under the Royal Prerogative (an executive power which does not require legislation). They can be withdrawn through the use of the same discretionary power.

The use of Royal Prerogative powers to withdraw a person’s passport was described as an important tool to disrupt individuals who plan to engage in fighting, extremist activity or terrorist training overseas and then return to the UK with those skills

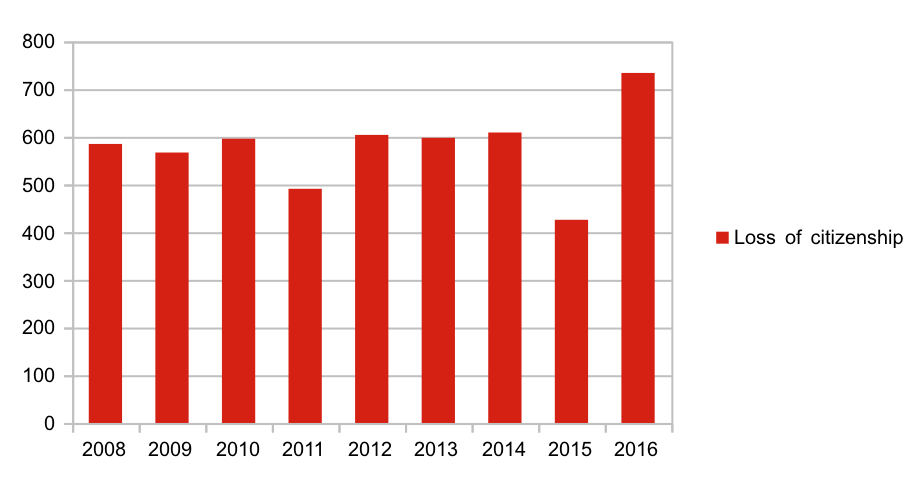

Loss citizenship in the UK

Between 2008 and 2016, some 5200 people have lost their citizenship in the United Kingdom according to EU citizenship acquisition statistics

What is Nullity?

Nullity, is the term used to describe a registration or naturalisation which was ineffective from the outset. This means the individual concerned does not need to be deprived of their British citizenship, as they are regarded as never having been granted it in the first place. The test for whether a registration or naturalisation was a nullity has been developed through case law and so is not set out in the legislation which deals with British nationality.

If it is concluded that a registration or naturalisation is a nullity, the Secretary of State will simply treat it as never having taken place and notify the individual accordingly. In such cases there is no need to use the statutory procedures for depriving a person of citizenship under section 40(2) and (3) of the British Nationality Act 1981. The Secretary of State need only be satisfied that the citizenship registration or naturalisation was not technically obtained in law.

A person whose citizenship is declared null and void has no statutory right of appeal, but could seek to challenge the decision by means of an application for judicial review. A decision to treat a person’s registration or naturalisation as a nullity could affect the position of that person’s spouse or other relatives whose own immigration or citizenship status was secured on the basis of the person’s claimed citizenship status. It might also render him or her liable to deportation or removal.

Where a person’s citizenship has been declared null and void, they will revert to their previous immigration status. If they still hold valid leave in an immigration category, this will continue provided we are satisfied that the criteria for granting such leave remains fulfilled. Equally, if they held indefinite leave to enter or remain before making their citizenship application, they will retain their settled status, provided we remain satisfied that all the relevant criteria were met when settlement was granted. The fact that someone initially retains their settled status following a declaration that their citizenship was a nullity does not prevent their indefinite leave to enter/remain being revoked at a later stage e.g. if the Secretary of State is satisfied that indefinite leave to enter/remain was obtained by deception.

Impact of nullity on the applicant’s children

A person whose registration or naturalisation is declared null and void is regarded as never having held that status. This will therefore impact on any children born following registration/naturalisation.

i. Children born in the UK

If the parent was settled in the UK prior to becoming a citizen, the child may be a British citizen.

ii. Children born overseas

As the parent was not a British citizen at the time of the birth, the child cannot be a British citizen by descent, and so will not have the right of abode in the UK. They will need to regularise their stay.

iii. Children registered when the parent registered or naturalised

Where the child registered as a British citizen on the basis of a false identity, then the registration is likely to be a nullity. Where the child registered as a British citizen in their true identity then, notwithstanding that the grant to the parent is a nullity, it would not be appropriate to take nullity action.

Read more about deprivation and nullity here